Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower

by Kate L. McCarter

Stephen Hopkins was born during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and came of age as England was experiencing great economic growth, increased overseas exploration, and a renaissance in the arts. Stephen was among the new class of Englishmen who left the countryside for London to become merchants, seamen, or settlers in the New World, but his adventuresome nature would eventually put him in a class by himself.

He was one of the first in Bermuda, where he survived shipwreck, mutiny, and near execution earning satirization in William Shakespeare's play The Tempest. He was one of the first in Jamestowne, the earliest permanent European settlement in North America, where he faced starvation, disease, and Indian attack. And sailing on the Mayflower, he was one of the first in New England, where he used his previous New World experience to shape the history of Plymouth Plantation.

In Hopkins of the Mayflower, Margaret Hodges writes, "Adventurers like Stephen broke the chains that bound Englishmen to a fixed and unalterable state of life in a fixed and unalterable society. In their ships they carried . . . ideas, planting the seeds of economic, social, and ethical thought that are with us yet."

Growing Up in Elizabethan England

Queen Elizabeth I Reigned

England from 1558-1603

Although Stephen Hopkins is a fairly well known figure in American history, much that has been written about his origins is incorrect. For years his biographers claimed that he had been born in Wortley, Wooton-under-Edge and had married Constance Dudley. Recent research by historian Caleb Johnson (1998) shows that Stephen was actually from Hursley, Hampshire and married to a woman by the name of Mary.

Stephen was probably born about 1579 in Hampshire. His parents may have been John and Elizabeth Hopkines of Winchester, Hampshire whose son, William, had a wife named Constance. Constance was an unusual name in Hampshire, so when Stephen gave this name to his second daughter, it may have been because of a family connection.

Items enumerated in a church inventory, after the untimely death of his wife, suggest that Stephen may have been a shop or tavern keeper.

Shipwrecking in Bermuda

In 1603 Queen Elizabeth I was succeeded by King James I, who chartered the Virginia Company of London to establish a colony in North America. The company was a consortium of businessmen whose objectives were to find gold and silver and a route to the Indies. To man the venture, the Virginia Company recruited everyone from gentlemen dreamers to prisoners who would gain their freedom after serving a term of indenture. Many recruits were veterans of the Spanish wars who had been beggared by the peace.

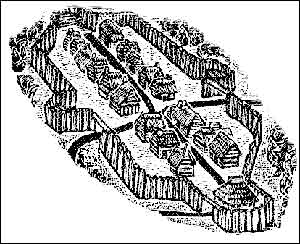

Jamestown Colony

Shakespeare's character Falstaff describes the would-be colonists as "ancients [ensigns], corporals, lieutenants, gentlemen of companies, slaves as ragged as Lazarus in the painted clothes . . . and such as, indeed, were never soldiers, but discarded unjust serving-men, younger sons to younger brothers, revolted tapsters [such as Stephen] and ostlers trade fallen, the cankers of a calm world and a long peace."

On May 14, 1607, the Virginia Company deposited about 100 men 35 miles inland on the James River in Virginia. They immediately set about making a colony at Jamestowne, but faced continual disappointment as mere survival became their primary aim.

They had the sheer misfortune of having arrived during the worst drought in 700 years, so growing crops was out of the question and safe drinking water was in short supply. The climate was hot and humid, and their fort sat in the midst of a malarial mosquito-infested swamp. The colony had been situated inland to avoid Spanish warships, but faced a greater threat from the native Algonquians headed by the powerful chief Powhatan.

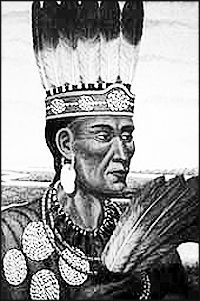

Also called Wahunsonacock, Powhatan was the leader of a large confederation of tribes that lived on the East Coast from Spanish Florida to the Potomac River. Powhatan's father had been driven north from Florida by the Spanish, so he had consolidated his tribe with six others. Powhatan expanded this confederacy until it consisted of about ten thousand people in thirty different tribes. The Algonquians opposed the English colonists and hostilities broke out on both sides with little provocation.

In all, the toll taken by disease, malnutrition, and violent death was appalling, and Jamestown was nearly wiped out in the first seven months. "Our men were destroyed with cruell disease as Swellings, Flixes, Burning Fevers, and by warres," wrote colonist George Percy. "Some departed suddenly, but for the most part they died of meere famine." The colony was saved from extinction by Captain John Smith who brought more men and supplies in 1608.

Chief Powhatan

A year later, Stephen left his wife and three small children in Hursley to sign on with the Third Supply, a fleet of nine ships taking 500 settlers and a mountain of supplies to Jamestown. Having no money to invest, and no rank of any kind, Stephen's name does not appear on the list of Virginia Company investors. Instead, he is lumped with the anonymous "sailors, soldiers, and servants" on the fleet's flagship, the Sea Venture. He is later described by William Strachey, who chronicled the voyage of the Sea Venture, as "A fellow who had much knowledge in the Scriptures, and could reason well therein" and therefore was chosen by Chaplain Richard Buck "to be his Clarke, to reade the Psalmes, and chapters upon Sondayes at assembly of the Congregation under him."

In a typical contract with the Virginia Company, Stephen would serve three years as an indentured servant, his labors profiting those who had financed the venture. In exchange, he would receive free transportation, food, lodging, and 10 shillings every three months for his family back home. At the end of three years, he would be freed from his indenture and given 30 acres in the colony.

On May 15, 1609, the Sea Venture, under the command of Sir George Somers, sailed down the Thames followed by the rest of the Virginia Company's fleet – the Falcon, Diamond, Swallow, Unity, Blessing, Lion, and two smaller crafts.

Hodges writes, "For seven weeks the ships stayed within sight of each other, often within earshot, and captains called to one another by way of trumpets. On the Sea Venture all was peaceful. Morning and evening, Chaplain Buck and Clerk Hopkins gathered the passengers and crew on deck for prayers and the singing of a psalm."

The ships were only eight days from the coast of Virginia, when they were suddenly caught in a hurricane, and the Sea Venture became separated from the rest of the fleet. William Strachey chronicled the Sea Venture's final days.

On St. James Day, being Monday, the clouds gathering thick upon us and the wind singing and whistling most unusually, a dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from out the northeast, which, swelling and roaring as it were by fits, at length did beat all night from Heaven; which like a hell of darkness, turned black upon us . . . For four-and-twenty hours the storm in a restless tumult had blown so exceedingly as we could not apprehend in our imaginations any possibility of greater violence; yet did we still find it not only more terrible but more constant, fury added to fury, and one storm urging a second more outrageous than the former . . .

The next day was worse. "It could not be said to rain," wrote Strachey. "The waters like whole rivers did flood in the air. Winds and seas were as mad as fury and rage could make them. Howbeit this was not all. It pleased God to bring greater affliction yet upon us; for in the beginning of the storm we had received likewise a mighty leak."

The ship had begun to take on water and every man who could be spared went below to plug the leaks and work the pumps. The men worked in waist-deep water for four days and nights, but by Friday morning they were exhausted and gave up.

Another chronicler, Silvester Jourdain, wrote that some of the men, "having some good and comfortable waters [gin and brandy] in the ship, fetched them and drunk one to the other, taking their last leave one of the other until their more joyful and happy meeting in a more blessed world." Then there was a crash and the Sea Venture began to split seam by seam as the water rushed in. Jourdain continues,

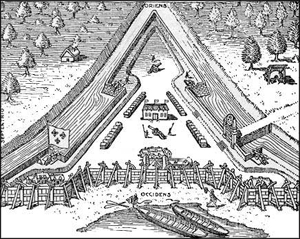

Wreck of the Sea Venture

And there neither did our ship sink but, more fortunately in so great a misfortune, fell in between two rocks, where she was fast lodged and locked for further budging; whereby we gained not only sufficient time, with the present help of our boat and skiff, safely to set and convey our men ashore . . .

The Sea Venture had been thrown upon a reef about a mile from Bermuda, then known as the "Isle of the Devils." Those who could swim lowered themselves into the waves and grasped wooden boxes, debris, or anything that would keep their heads above water. Stephen made it to shore clutching a barrel of wine. The entire crew, including the ship's dog, survived.

As it turned out, the Sea Venture did not break apart and the men were able to retrieve the tools, food, clothing, muskets, and everything that meant their survival. Most of the ship's structure also remained, so using the wreckage and native cedar trees, the 150 castaways immediately set about building two new boats so that they could complete their voyage to Jamestown.

The men were pleasantly surprised to find that the island's climate was agreeable, food plentiful, and shelters easily constructed from cedar wood and palm leaves. The Isle of the Devils, turned out to be paradise, and a few began to wonder why they should leave. Strachey recounts that some of the sailors, who had been to Jamestown with the Second Supply, stated that "in Virginia nothing but wretchedness and labor must be expected, there being neither fish, flesh, or fowl which here at ease and pleasure might be enjoyed."

The first attempt at mutiny was made by Nicholas Bennit who "made much profession of Scripture" and was described by Strachey as a "mutinous and dissembling Imposter." Bennit and five other men escaped into the woods, but were captured and banished to one of the distant islands. The banished men soon found that life on the solitary island was not altogether desirable and humbly petitioned for a pardon, which they received. But the clemency of the Governor only encouraged the spirit of mutiny. William Strachey notes that while Hopkins was very religious, he was contentious and defiant of authority and had enough learning to wrest leadership from others. On January 24, while on a break with Samuel Sharpe and Humfrey Reede, Stephen argued,

. . . it was no breach of honesty, conscience, nor Religion to decline from the obedience of the Governor or refuse to goe any further led by his authority (except it so pleased themselves) since the authority ceased when the wracke was committed, and, with it, they were all then freed from the government of any man . . .[there] were two apparent reasons to stay them even in this place; first, abundance of God's providence of all manner of good foode; next, some hope in reasonable time, when they might grow weary of the place, to build a small Barke, with the skill and help of the aforesaid Nicholas Bennit, whom they insinuated to them to be of the conspiracy, that so might get cleere from hence at their own pleasures . . . when in Virginia, the first would be assuredly wanting, and they might well feare to be detained in that Countrie by the authority of the Commander thereof, and their whole life to serve the turnes of the Adventurers with their travailes and labors.

The mutiny was brought to a quick end when Sharpe and Reede reported Stephen to Sir Thomas Gates who immediately put him under guard. That evening, at the tolling of a bell, the entire company assembled and witnessed Stephen's trial.

. . . the Prisoner was brought forth in manacles, and both accused, and suffered to make at large, to every particular, his answere; which was onely full of sorrow and teares, pleading simplicity, and deniall. But he being onely found, at this time, both the, Captaine and the follower of this Mutinie, and generally held worthy to satisfie the punishment of his offence, with the sacrifice of his life, our Governour passed the sentence of a Maritiall Court upon him, such as belongs to Mutinie and Rebellion. But so penitent hee was, and made so much moane, alleadging the ruine of his Wife and Children in this his trespasse, as it wrought in the hearts of all the better sorts of the Company, who therefore with humble entreaties, and earnest supplications, went unto our Governor, whom they besought (as likewise did Captaine Newport, and my selfe) and never left him untill we had got his pardon.

After pleading his way out of a hanging, Stephen continued his duties as Minister's Clerk and worked quietly with the others to finish the construction of the ships. On May 10, 1610, the men boarded the newly built Deliverance and Patience and set out for Virginia. They arrived in Jamestown on May 24, almost a full year after they had left England.

Surviving Jamestown

James Fort

What the Sea Venture's crew found when they reached Jamestown undoubtedly made them grateful to have been shipwrecked.

Over the winter, food had become so scarce that the settlers had been compelled to eat their horses, dogs, and even the flesh of those who had died. Only 50 of the 500 colonists remained. In contrast, the Bermuda crew were well-fed and healthy.

Strachey wrote of Jamestown, "the palisades torn down, the ports open, the gates off the hinges, and empty houses rent up and burnt, rather than the dwellers would step into the woods a stone's cast off to fetch other firewood. The Indians killed as fast, if our men but stirred beyond the bounds of their blockhouse, as famine and pestilence did."

The new arrivals calculated that the meal cakes they had brought with them would feed everyone for no longer than ten days. So it appeared that abandonment of the settlement was their only hope. The plan was for all to board the Patience and Deliverance and sail up the coast to Newfoundland where, at this time of year, they could find fishing vessels to take them home to England. They anchored that night off an island near the mouth of the James. The next morning they were surprised by an approaching longboat which brought the news that Lord Delaware was following with three shiploads of settlers and provisions to feed 400 for a year. The settlers from Jamestown returned to the abandoned colony and were at the gate of the fort to welcome the new governor when he dropped anchor on June 10th.

Delaware immediately set about restoring the broken down fort. By midsummer the gate and palisade were repaired, and there was a new chapel and three rows of houses inside the triangular fort. Jamestown finally seemed to be on solid footing.

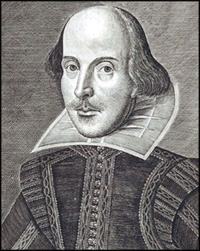

William Shakespeare

In the meantime, Strachey's account of the wreck of the Sea Venture had made it back to England. Strachey was no stranger to the theater people who met regularly at the Mermaid Tavern, so it's probable that Shakespeare was among those who got a preview of the work. Some believe he used it as the basis for his farewell play, The Tempest, which relates the story of a shipwrecked group stranded on an enchanted island. In a play to be performed for the King, a rebel could only be shown as a clown or a villain, so Shakespeare created a drunken, mutinous butler (or bottler) with delusions of grandeur who he named Stephano.

Hodges writes, "To have provided some of the fabric for Shakespeare's vision of The Tempest and to appear in the play, even in the absurd disguise as Stephano, this in itself is a kind of immortality for Stephen Hopkins."

Several years later, the Virginia Company published a heavily sanitized version of Strachey's A True Reportory fearing that if the public knew the truth about Jamestown, there would be no more recruits.

Stephen does not appear on any of the lists of Jamestown colonists and, after his attempted mutiny, the assumption is that he was put on the first ship back to England. However, he is not in England in 1613 when his wife dies, and his later familiarity with Indians in Plymouth suggests that he may have spent several years in Jamestown.

Pocahontas Marries John Rolfe

During these years (1610-14), survival remained the primary aim of the Jamestown colonists. The climate was unhealthy for Englishmen who were used to northern latitudes, and the settlers were constantly afflicted with "fluxes and agues." The Indians also posed a continual threat until April 5, 1614 when John Rolfe married Pocahontas, the daughter of Chief Powhatan. If Stephen had managed to get back into the good graces of the Jamestown authorities, it's not unreasonable to assume that he may have assisted Master Buck in performing the wedding ceremony.

Returning to England

In the spring of 1613, Stephen's wife, Mary, died. She may have been a victim of the plague which was still rampant in certain parts of England. With Stephen absent and presumed dead, the Church liquidated the couple's estate to provide for the children.

An inventory of the goods and Chattells of Mary Hopkins of Hursley in the Countie of South[amp]ton widowe deceased taken the tenth day of May 1613 as followeth vizt.

Inprimis certen Beames in the garden & wood in the back side

It[e]m the ymplem[en]ts in the Beehouse

It[e]m certen things in the kitchin

It[e]m in the hall one table, one Cupboorde & certen other things

It[e]m in the buttry six small vessells & some other small things

It[e]m brasse and pewter

It[e]m in the Chamber over the shop two beds one table & a forme with some other small things

It[e]m in the Chamber over the hall one fetherbed & 3 Chests & one box

It[e]m Lynnen & wearing apparrell

It[e]m in the shop one shopboarde & a plank

It[e]m the Lease of the house wherin she Late dwelled

It[e]m in ready mony & debts by specialitie & without specialitie

S[um] total xxv xj [25 pounds 11 shillings]

Gregory Horwood (his X mark)

William Toot

Rychard Wolle

Stephen returned home sometime between 1613-17, perhaps with the intent of selling his belongings in England and bringing his family to their new home in Virginia. After having survived shipwreck and the perils of Jamestown, it must have been a great blow to find his wife and estate gone, and his children entrusted to the care of the Church.

By late 1617 Stephen and his children had settled into a home just outside of the east wall of London, where he was said to be working as a tanner. On February 9, 1618, in the local church of St. Mary Matfellon in Whitechapel, he married his second wife, Elizabeth Fisher. In late 1618 Elizabeth and Stephen added another child to the family – a daughter they named Damaris.

William Brewster

Nearby the Hopkins' home was the Henage House – a mansion that had been converted into apartments which housed a number of nonconformists. Among these were Robert Cushman, John Carver, and William Brewster, members of the Scrooby Separatist congregation who had fled to Leyden, Holland years earlier to escape religious persecution. The three had returned to raise money for a patent to create a settlement in the New World for their congregation now living in exile in Holland

The dissenters movement had begun about 40 years earlier when Cambridge scholar Robert Browne began preaching sermons denouncing the Church of England as "a huge mass of old and stinking works," and accusing its members of "conjuring, witchcraft, sorcery, blasphemy, murder, manslaughter, robberies, adultery, fornication, and lieing." Because church attendance was mandatory for all English citizens, Browne's remarks, while somewhat hyperbolic, may not have been too far off the mark.

The dissenters were true-believers who generally fell into either the Separatist or Puritan camps. In general, the Separatists' views were not as extreme as the Puritans' in regard to social customs. They dressed in the bright colored clothing of the period, drank alcohol, attended plays, and danced. They were, however, more extreme when it came to separating ties with the Church of England. The Puritans believed that the established church could be reformed. The Separatists held that membership in the Church of England violated the biblical precepts for true Christians, and that they had to break away and form independent congregations. At a time when Church and State were one, such beliefs were treasonous.

William Bradford

William Bradford, an orphan boy adopted by the Brewsters and eventual governor of the Plymouth Colony, tells of the abuse suffered by the Scrooby Separatist congregation before they fled to Leyden. "They were hunted and persecuted on every side. Some were taken and clapped up in prison, others had their houses beset and watched day and night, and most were fain to flee and leave their houses and habitations, and the means of their livelihood." In the end the little group did abandon their homeland for Holland, where religious tolerance was the rule.

In Leyden, the Scrooby Separatists found no barriers to practicing their faith. However, as foreigners, they were at the bottom of the economic ladder and had to put their children to work simply to survive. They feared the negative influence of the Dutch on their children, and the loss of their English traditions. They also worried about the threat of renewed war between the Dutch and the Spanish, which could bring the loss of their religious freedom.

So in the summer of 1618 the little congregation made the decision to emigrate yet again. John Carver, Robert Cushman, and William Brewster were sent to London to try to get financial backing for a Separatist settlement in America.

To settle in the New World required a patent (license to colonize) and backing by investors. The Separatists rejected an offer to settle under the auspices of the Dutch Government in New Amsterdam and instead approached King James who refused to give them an official patent, but said that if they went to Jamestown he "would not molest them, provided they carried themselves peaceably." The Separatists feared that they would be persecuted if they joined the English colony in Virginia, so rejected this offer too.

Finally Thomas Weston, a London merchant, offered a proposal. He had heard that the Plymouth branch of the Virginia Company had asked for a patent to settle "Northern Virginia" at the mouth of the Hudson River. This seemed like a good location for the Separatists because it was far away from Jamestown and the established Church, and was near the more tolerant Dutch settlements.

A group of English investors known as "merchant adventurers" agreed to finance the voyage and settlement. They formed a joint-stock company with the colonists in which they would "adventure" or risk their money in exchange for the settlers' personal labor for a period of seven years. During that time, all land and livestock were to be owned in partnership. At the end of seven years, the company would be dissolved and the assets divided.

Weston found seventy investors, but in the end only a small number of Separatists were willing to risk their lives making a dangerous voyage to an unknown land. Weston solved the problem by recruiting others who were sympathetic to the Separatist cause, but were primarily interested in relocating in the New World for economic reasons. One of those he approached was his neighbor, Stephen Hopkins. With his previous New World experience, Stephen knew much that would be of use to the future colonists. He agreed to the new venture, but this time would not be leaving his family behind.

The voyage was set for early spring so that the colonists would arrive in the New World in time to prepare for winter. But there were many delays and the spring of 1620 came and went, and it was July before the Separatists left Leyden in their small ship, the Speedwell. They sailed to Southampton, a city on the English south coast, where they were joined by the investors and the non-Separatists recruited by Weston. For their primary transportation, the investors had hired the Mayflower, a larger ship that had been used in the wine trade.

Pilgrims Set Sail for the New World

The Separatists hoped to fulfill their contract with the investors by becoming fishermen, but some of the more experienced men, such as Stephen, realized the group was ill-prepared. They had purchased fish hooks that were too large and nets that were too weak, and brought almost nothing to trade with the Indians. When Robert Cushman arrived at Southampton, he was advised to buy more muskets and armor, as well as copper chains, beads, knives, scissors, and other things to trade with the natives.

Disagreement over the contract brought another delay. The original plan called for the colonists to work five days a week for seven years to pay their debt. In the end they would own their houses and a share of the land worth 10 pounds. After five weeks of pressure from the investors, Cushman signed a new agreement in which the colonists would work seven days a week for seven years to pay their debt and would own nothing privately, not even the roofs over their heads. Under the new agreement they would risk their lives and work like slaves for seven years with nothing to show for it but their share of land. They also learned that Weston had no clear patent from the Virginia Company and had not even invested his own money in the enterprise.

There had never been a more poorly planned and supplied venture, but the settlers were willing to forge ahead. On August 5, 1620, they boarded the two ships and set sail for the New World.

Their voyage was soon interrupted, however, when the smaller Speedwell began leaking. They put into the port at Dartmouth and made repairs, but the condition recurred once they were under sail again. They managed to make it to port in neighboring Plymouth where they decided to abandon the unreliable ship. The already crowded Mayflower could take on only a few of the Speedwell's passengers, so the rest had to return to Leyden. Only 35 of the Separatists remained. The other 67 Mayflower passengers were the non-Separatist Londoners who had been recruited by Weston. On September 6, 1620, these Pilgrims (Separatists and non-Separatists alike) set sail across the North Atlantic headed for the northernmost boundary of the Virginia colony.

Sailing on the Mayflower

A Prosperous Wind by Mike Haywood

The Hopkins family was one of the largest aboard with Stephen, his wife Elizabeth, the children Constance, Giles, and Damaris, and their two servants Edward Doty and Edward Leister. The family grew even larger when Elizabeth gave birth to their son, Oceanus, while they were still at sea. The fate of Stephen's oldest child, Elizabeth, is unknown. She may have died or, being of age, may have decided to stay in England.

The pilgrims spent most of the voyage in the dark quarters on the gun deck. One side of the deck was taken up by a shallop (boat) which was essential for landing and exploring. On the other side, they nailed up compartments for the women and children of each family. The men slept wherever they could hang a hammock. Many ended up in the shallop. They occasionally went up for air on the upper deck, but the Mayflower's longboat filled most of the space and the crew was often unfriendly.

At the end of September, the Mayflower was caught in an equinoxial storm. The pilgrims mattresses and clothes were soaked, and they were chilled to the bone. Their cooking fires were doused, so they had to make do with dried beef, biscuits, and cheese for the rest of the voyage.

Ship was Shroudly Shaken by Mike Haywood

They were about halfway across the ocean when fierce crosswinds cracked one of the main beams leading to severe leaks in the upper works. The passengers from Leyden saved the day by bringing forth a great jackscrew meant for raising houses. They used it to force the Mayflower's beam back into place and make the ship sound again. The storms finally eased, and the Mayflower's sails were raised to a favoring wind.

When the Mayflower sighted land on November 9, 1620, first mate John Clark recognized the shoreline of Cape Cod, which was north of their original destination of the mouth of the Hudson River. The crew changed course, but after encountering some dangerous shoals and nearly shipwrecking at Monomoy Point, they returned to the Cape.

On November 11, after 66 days at sea, the Mayflower came to anchor in what is now Provincetown harbor, and Stephen once again found himself on a ship which had reached an unintended destination.

Riptide Off Monomoy Point by Mike Haywood

Some of the settlers wanted to continue the search for the mouth of the Hudson. Others argued for remaining in the Cape where they would be free to do as they pleased. Stephen, despite his near execution for treason in Bermuda, was among the latter.

Governor William Bradford in Of Plymouth Plantation wrote of the difficulty, "ye discontented & mutinous speeches that some of the strangers [non-Separatists] amongst them had let fall from them in ye ship – That when they came a shore they would use their own libertie; for none had power to command them, the patente they had being for Virginia and not for New England which belonged to an other government, with which the ye Virginia Company had nothing to doe. And partly that shuch an acte by them done (this their condition considered) might be as firme as any patent, and in some respects more sure."

The issue was finally resolved by Captain Jones who brought the Mayflower into a harbor off the northwest shore of Cape Cod and let the anchor go. Unwilling to risk the Mayflower in a midwinter search for the Hudson, he suggested they settle where they were.

Signing of the Mayflower Compact

The forty-one adult male passengers gathered in the cabin of the Mayflower to decide what to do next. With the help of William Brewster's book of law, they formulated and signed the Mayflower Compact which consolidated the passengers into a "body politic" that had the power to enact laws for the settlement. The compact also established the rule of the majority, which remained a primary principle of government in Plymouth Colony until it became part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691.

Then the longboat was launched, and sixteen men equipped with muskets, swords, and corselets went ashore under Captain Miles Standish "unto whom was adjoined, for counsel and advice, William Bradford, Stephen Hopkins, and Edward Tilley," wrote Bradford.

Stephen was one of only three who had been to the New World before. Now in his forties, he was one of the seniors of the expedition, both in age and experience, so it is not surprising that he would become one of Standish's chief aides.

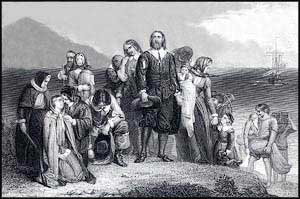

Bradford continues, "Being thus arrived in a good harbor, and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element."

Founding Plymouth Plantation

The Mayflower remained anchored in the harbor as the passengers were taken ashore to walk off the months of travel, bathe, and wash their clothing and linens. As some of the colonists assembled the shallop, Captain Standish and his sixteen armed men continued to explore the immediate area to find a satisfactory site for the colony.

They saw some Indians from afar, but were unable to catch up with them. They found the remains of a fortification and discovered a buried cache of corn which they took. Mourt's Relation, an account of the pilgrim's first year in Plymouth, tells how the group "came to a tree where a young spirit [sapling] was bowen down over a bow, and some acorns strewed underneath, Stephen Hopkins said it had been to catch some deer." While he was explaining how it worked, William Bradford came from the rear to look. "As he went about, it gave a sudden jerk up, and he was immediately caught by the leg."

Pilgrim's Landing

After the shallop was assembled, 34 men joined the second expedition which explored further along the inner Cape. They found many signs of the native population which had fled at their approach. They also found more corn and the burial site of a European man.

While the men explored the coastline, the women were left on board the Mayflower to worry about the fate of their husbands, and contend with spreading sickness brought on by dampness, cold, and malnutrition. The colonists had to settle somewhere soon.

One of the ship's crew knew of a good inlet further along the coast that the sailors called "Thievish Harbor." On December 6, Stephen was one of ten men that braved the frigid weather to take the shallop along the coast. They found an Indian burial ground and some unoccupied dwellings before camping for the night. At daybreak they were attacked by members of the Nauset tribe. There was a brief exchange of arrows and musket shot, but no one was harmed. They got back in their boat and rowed on in hopes of finding the harbor.

That afternoon they were caught in a rising storm which broke the rudder hinges and the mast. One of the Mayflower's mates managed to maneuver the shallop into a nearby harbor where they landed on an island and spent a cold and rainy night. The following day being Sunday, they did little but explore the island.

On Monday, the 11th of December, they located "Thievish Harbor" and went ashore. Although there is no record of it in the original accounts, this is when the famous landing on Plymouth Rock was supposed to have occurred. The explorers found plenty of fresh running water and cleared fields, but no Indians. They learned why after hiking for several miles and encountering the skeletons of a tribe that had been decimated by disease.

They returned to the Mayflower with the news that they had, at last, found a suitable place to build their new community. The Mayflower arrived in the harbor on December 16, 1620.

Their first task was to draw up plans for the settlement which would include nineteen houses, a common house, and a storage shed. The single men would live with families, and the houses would vary in size according to the number in each family. On the hill above the village, they erected a platform with six cannons for defense.

Building the Common House

On December 29 twenty men, including Stephen and his servants, began building the common house. The wind and rain constantly put a stop to their work, but by mid-January, despite hunger and bad weather, the 20-by-20 foot common house was nearly complete.

The Mayflower remained anchored in the harbor throughout the winter. Although the ship was cold, damp, and unheated, it was their only shelter until the houses could be completed on shore. Exposure, malnutrition, and illness began taking their toll. Stephen had escaped the "starving time" at Jamestown, but he did not escape this one. William Bradford wrote,

In two or three months' time half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases which this long voyage had brought up on them, so as there died sometimes two or three of a day. Of 100 and odd persons, scarce fifty remained. And of these, in the time of most distress, there was but six or seven sound persons who to their great commendations spared no pains night or day, but with abundance of toil and hazard to their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them.

The women were the hardest hit with only four of eighteen surviving. By some miracle, the Hopkins family and their servants were spared. In March some of the sick began to recover, and those who were able began to plant their gardens. A grateful Bradford wrote, "the Spring now approaching, it pleased God the mortalitie begane to cease amongst them, and the sick and lame recovered apace, which put as it were new life into them; though they had borne their sadd affliction with much patience & contentednes."

In early April, the Mayflower returned to England with a small cargo of beaver skins and sassafras. Not one of the pilgrims chose to return to England. William Bradford would later write, "May not and ought not the children of these fathers rightly say: Our fathers were Englishmen which came over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in this wilderness; but they cried unto the Lord, and He heard their voice and looked on their adversity."

Meeting the Natives

Having learned a great deal from his experiences in Bermuda and Jamestown, Stephen quickly proved his worth to the colony. While skilled as a hunter and fisherman, his biggest contribution was his ability to relate to the native people. The Hopkins home became an embassy where Indian chiefs were entertained, and Stephen was asked to participate in several important trips to Indian settlements in the summer of 1621.

As early as mid-February, the settlers had spotted Indians "skulking about the settlement," but it wasn't until mid-March that the groups finally met. In this well-known encounter, the men were going through their military instructions, when an Indian man walked right into the settlement and bade them "welcome" in their own language. He was Samoset, a Sagamore from Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine.

Pilgrims Meet Samoset

Samoset was taken to the Hopkins house where he was given a meal of the best they had to offer – brandy, roast duck, biscuits and cheese, and corn pudding. Over dinner Samoset explained that he had learned their language from the Englishmen who crossed the North Atlantic each year to fish for cod. He had heard about the pilgrim's arrival and, for some time, had been traveling south to meet them.

He explained that the Nausets, with whom the colonists had skirmished, harbored ill-feelings toward the English because Captain Thomas Hunt, an English slave-trader, had kidnapped some of their people a few years earlier.

Samoset also revealed that the tribe that had once lived here had been wiped out by smallpox brought by the English. The only survivor was Squanto, one of the men who had been captured by Hunt. Squanto had made his way back to his homeland, and Samoset promised to bring him on his next visit. Samoset spent the night with the Hopkins and left the next day with gifts of a knife, bracelet, and ring.

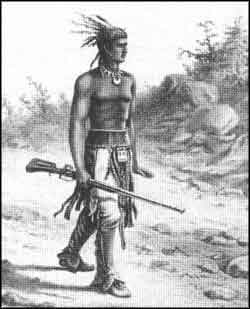

On March 22, Samoset returned with Squanto whose adventures abroad had taught him a great deal about the ways of the Europeans. Being a man without a home, family, or tribe, Squanto settled in with the Hopkins and became the colony's agent in their interaction with the local tribes. His arrival paved the way for a visit by Woosamequin 'Yellow Feather' also known as Massasoit the 'great chief' of the Wampanoag.

Massasoit and Gov. Carver Sign a Treaty

On the day of his arrival, Massasiot was escorted to the Hopkins house. After eating and exchanging gifts, Massasoit and Governor Carver began negotiations. The Wampanoag had powerful enemies in the Narragansetts, and wanted the Englishmen as allies. Being so few in number, the colonists also needed allies, so the two signed a peace treaty stating that they would come to each other's aid in the event of attack from outsiders. It was a momentous occasion. The peace agreement made in the Hopkins home that day would stand for more than fifty years.

In the spring the settlers began planting their crops. Squanto showed them how to make the most of their corn by planting it in mounds, using fish as fertilizer. Gov. John Carver was hoeing in the corn fields one day, when he suffered a stroke and died shortly afterward. The colony then elected William Bradford to rule over what remained of their fragile colony.

In July Governor Bradford asked Stephen, Squanto, and Edward Winslow to locate Packanokik, the settlement of chief Massasoit, so that they would be able to call on him quickly in time of need. They also wanted to determine the size and strength of his community and to renew the "league of peace and friendship" they had established with the Wampanoags. Winslow kept a record of their journey which would later appear in Mourt's Relations.

On the first day of their expedition, they met a dozen Indians who "pestered" them until they "grew quite weary." The Indians led them to Nemasket where they were entertained and fed a kind of bread. The Indians asked that the men shoot at a crow, complaining about the damage the birds were doing to their corn. One of the men impressed them with his marksmanship by killing the bird from some "forescore off."

Squanto lived with the Pilgrims for 18

months. He died of a fever in 1622.

They continued on their journey and by evening came to a wide river, where they found many Indians fishing at a dam. They exchanged their provisions for a meal of fresh fish, and spent the night in the open fields as the Indians did in the summer. The next morning they were joined by six "savages" who "proved friendly." The Indians showed them where to ford the rivers and offered to carry them over even the smallest stream. When either of the Englishmen looked weary, their guides offered to carry their provisions, and even their clothes. They ran into others on the trail who gave them fresh water, roasted crabs, oysters, and other fish.

Eventually they reached Massasoit's village, but he was not at home. Winslow wrote that they "found the place to be 40 miles from hence, the soyle good, and the people not many, being dead and abundantly wasted in the late great mortalitie which fell in all these parts aboute three years before the coming of the English, wherein thousands of them dyed, they not being able to burie one another; their sculs and bones were found many playces lying still above ground, where their houses and dwellings had been; a very sad spectackle to behould."

When Massasoit returned, the Englishmen greeted him by firing their guns in salute. He welcomed them into his house, where Squanto acted as interpreter. They gave Massasoit a red cotton horseman's coat and copper necklace, which he immediately donned and modeled for the entertainment of his tribe.

As diplomat, Winslow suggested that Massasoit's people should only come to Plymouth with the consent of the chief, since the colony was short of food and could no longer entertain an unlimited number of guests. They also stated that they wanted to repay the Nauset for the corn they had taken from their mounds, and asked if Massasoit would send word to them. Winslow also asked for trading goods, such as beaver skins, which could be sent back to England.

Massasoit agreed to all their requests and gave a lengthy speech explaining the matter to his people and naming all thirty of his villages that were bound by the agreement. He ended his speech after pledging loyalty to the English King, and telling the pilgrims that he felt sorry for King James whose wife, Queen Anne, had died in 1619. He then lit tobacco for them, and they discussed matters in England, particularly how the King was getting along without a wife.

Woosamequin or Massasoit

'Great Chief' of the Wampanoag

When the group retired, Stephen and Winslow were invited to join the chief and his wife in their bed. By custom, the bed had to be full, so two other tribal leaders crowded in the remaining space. The four Wampanoags quickly put themselves to sleep through rhythmic chanting, but the Pilgrims had a restless night. The bed was full of lice and fleas, but moving outside meant they would be eaten alive by mosquitoes. Winslow later complained that they were more weary "of their lodging, than of their journey."

The next day the Wampanoags held games with beaver skins as prizes. The pilgrims didn't participate, but were asked to demonstrate their skills as marksmen. At noon forty men gathered to share a meager lunch of three large fresh water fish. The Pilgrims spent another night with the Wampanoags, but told the chief they must be returning home to keep the Sabbath.

They rose before sunrise the next day and departed with the six Indians who had brought them. They shared the last of their food with their guides who surprised them the next morning with a breakfast of fresh fish. They were caught in a "great storm" on the last day and reached Plymouth wet and weary, but elated with success.

Stephen and Squanto had barely recuperated from their trip, when they were asked to join a search party to find young John Billington. They soon learned that he had been found in the woods by the unfriendly Nausets, so they gathered their courage and rowed the shallop to the Nauset village.

Hearing that the pilgrims were coming, Chief Aspinet met the boat with "no less than a hundred of his men," but the colonists had nothing to fear. With Squanto's help, they understood that the pilgrims had come in peace and wished to pay for the corn they had taken. A great train of men then carried the boy through the water to the boat unharmed and bedecked with beads. The colonists thanked Chief Aspinet and the man who had found Billington with gifts of knives.

Celebrating the First Thanksgiving

As summer ended, the settlers took stock of their situation. Their crops were successful and, if their other food gathering efforts proved effective, they could survive a second winter. William Bradford wrote,

The First Thanksgiving

They begane now to gather in ye small harvest they had, and to fitte up their houses and dwellings against winter, being well recovered in health & strenght, and had all things in good plenty; for some were thus imployed in affairs abroad, others were excersised in fishing, aboute codd, & bass, & other fish, of which yey tooke good store, of which every family had their portion. All ye somer ther was no wante. And now begane to come in store of foule, as winter aproached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degree). And besids water foule, ther was great store of wild Turkies, of which they took many, besids venison, &c. Besids they had aboute a peck a meale a weeke to a person, or now since harvest, Indean corne to yt proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largly of their plenty hear to their freinds in England, which were not fained, but true reports.

For the first time in months, the threat of starvation had passed, and they could relax and enjoy the results of their efforts with their friends and neighbors. In a letter, Edward Winslow describes the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth.

Our Corne [wheat] did prove well, & God be praysed, we had a good increase of Indian Corne, and our Barly indifferent good, but our Pease not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sowne, they came up very well, and blossomed, but the Sunne parched them in the blossome; our harvest being gotten in, our Governour sent foure men on fowling, that so we might after a more speciall manner reioyce together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors; they foure in one day killed as much fowle, as with a little helpe beside, served the Company almost a weeke, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest King Massasoyt, with some nintie men, whom for three dayes we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deere, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed upon our Governour, and upon the Captaine, and others. And although it be not alwayes so plentifull, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodneses of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.

Expanding Plymouth Plantation

The Fortune

In November of 1621 the Fortune arrived with thirty-five new settlers, but no supplies. Robert Cushman carried a terse letter from Thomas Weston asking the colonists why they had run up expenses by keeping the Mayflower at Plymouth all winter, and why they had not filled her hold with more cargo for the return trip. Then, because some of the non-Separatists had begun to press for individual property rights, Cushman gave a sermon comparing their "worldly ambition" to the "pride of Satan."

The colonists survived the second winter, despite the thirty-five extra mouths to feed, and enjoyed an even better harvest in the fall of 1622. More settlers continued to arrive in ships like the Anne and Little James, so by 1623 most of the original Leyden congregation had made it to Plymouth. William Bradford wrote of the shock many of the newcomers felt when they finally reached Plymouth,

These passengers, when they saw their [the original settler's] low & poore condition a shore, were much daunted and dismayed, and according to their divers humores were diversly affected; some wished them selves in England againe; others fell a weeping, fancying their own miserie in what they saw now in others; other some pitying the distress they saw their friends had been long in, and still were under; in a word, all were full of sadness.

As Plymouth grew, it gained many more non-Separatist colonists who often had difficulty adhering to the laws established by the first-comers. Some of the more rebellious were even expelled from the settlement. The non-Separatists who remained in Plymouth disagreed with the Separatists from time to time, but the groups continued to work together to make the colony prosper.

In 1624 Captain John Smith visited Plymouth and reported, "At New Plymouth is about 180 persons, some cattle and goats, but many swine and poultry, and thirty-two dwelling houses." The houses which lined Plymouth's main street were made in the traditional English manner with clapboards, wattle and daub, and oil-paper windows.

The Hopkins home sat across from Governor Bradford's on the eastern corner of Main and Leyden. It was one of the largest houses in Plymouth to accommodate its large family. By 1627 each house had a fenced garden with flowers and herbs. The Hopkins also had a barn, dairy, cow shed, and small apple orchard. Both Damaris and Oceanus died around 1626, but five new children, Caleb, Deborah, Damaris (again), Ruth, and Elizabeth, were born between 1622 and about 1630. Constance moved out in 1628 when she married carpenter Nicholas Snow who had sailed on the Anne.

Stephen had been an early proponent of the fur trade, so expanded his house to include a store where the Indians could come and trade beaver skins for English goods. In 1624 when ships began importing wine, beer, brandy, and gin, Stephen added a tavern.

He also built and owned the first wharf in Plymouth Colony, and in 1638 built a house at Yarmouth on Cape Cod, but soon returned to Plymouth. He gave the Yarmouth dwelling to Giles, who had married Catherine Wheldon in 1639.

Between 1623 and 1638, Stephen made numerous appearances in Plymouth Colony records.

In the 1623 Plymouth division of land, "Steven Hobkins" received six acres as a passenger of the Mayflower.

In the 1627 Plymouth division of cattle, Stephen is listed with his wife Elizabeth, and children Gyles, Caleb, Deborah, and Damaris.

In the 1633 list of Plymouth freemen (those who were entitled to citizenship and other special privileges in the colony), Stephen is near the head of the list, included among the Council Assistants.

On July 1, 1633 "Mr. Hopkins" was ordered to mow where he had mowed the year before, followed by similar orders on March 14, 1635 and March 20, 1636.

In the Plymouth tax list of March 25, 1634 Stephen was assessed £1 7s.

In the list of Plymouth Colony freemen, March 7, 1636, he appears as "Steephen Hopkins, gent."

On February 5, 1637 "Mr. Stephen Hopkins requesteth a grant of lands towards the Six Mile Brook."

On July 17, 1637 "Stephen Hopkins of Plymouth, gent.," sold to George Boare of Scituate, yeoman, "all that his messuage, houses, tenements, outhouses lying and being at the Broken Wharfe towards the Eele River together with the six shares of lands thereunto belonging containing six acres."

On August 7, 1638 "liberty is granted to Mr. Steephen Hopkins to erect a house at Mattacheese, and cut hay there this year to winter his cattle, provided that it be not to withdraw him from the town of Plymouth."

On November 30, 1638 "Mr. Steephen Hopkins" sold to Josias Cooke "all those his six acres of land lying on the south side of the Town Brook of Plymouth."

On June 1, 1640 "Mr. Hopkins" was granted twelve acres of meadow.

On June 8, 1642, William Chase, in consideration of a debt of £5 which he owed to Stephen, mortgaged to him "his house and lands in Yarmouth containing eight acres of upland and six acres more lying at the Stony Cove."

Contending with New Neighbors

Massachusetts Bay 1630-1642

Eight years after the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, a group of colonists under Governor John Endicott sailed into Massachusetts Bay. They were followed two years later by the eleven ships of the Winthrop fleet, which represented a far greater investment of time, energy, and money than had been spent on neglected Plymouth. The pilgrims undoubtedly looked on with some envy as the new colonists quickly established villages at Boston, Salem, Cambridge, Watertown, and Charlestown.

As the English began to pour into New England, tensions with the Indians mounted, particularly after the Indians began buying alcohol and firearms from unscrupulous adventurers. One of the worst was Thomas Morton who had arrived and taken control of a nearby plantation at Mount Wallarton, which he appropriately renamed "Merry Mount."

William Bradford wrote that Morton and his followers, mostly outcasts from Plymouth, "set up a maypole with much drinking, dancing, and consorting with the Indian women . . . after this they all fell to a great licentiousness and from then on led a most dissolute life." To make matters worse, the pleasure-seekers traded their guns to the Indians for food rather than interrupt their activities to go hunting.

The Indians soon became crack shots and, with little provocation, began to shoot at the English. The men at Plymouth felt that it was a matter of self-preservation to put an end to this gun trade, and Stephen was second in command of the expedition to wipe out Merry Mount. The raiding party caught Morton and his men off guard, disarmed them, and sent Morton back to England on the next ship. But even with Merry Mount gone, the Indians still had their weapons and major conflict seemed inevitable.

The Pequot War

The Pequot War of 1637, the first major conflict between Indians and colonists in New England, set a brutal precedent for subsequent Indian-European warfare. The Pequots were accused of murdering two Massachusetts Bay colony men, and refused to yield up the suspected killers. Colonial authorities decided to retaliate, a decision reinforced by Pequot resistance to new Connecticut settlements. On May 26, 1637, a force of white soldiers, along with Mohegan and Narragansett warriors, attacked the principal Pequot village, burned it, and slaughtered its inhabitants. The surviving Pequots were relentlessly pursued, until the tribe was largely destroyed.

Hodges writes, "When Massachusetts Bay called on Plymouth for help, the older colony was reluctant. Like most men at Plymouth, Stephen Hopkins was opposed to the Pequot War. It not only threatened the physical safety of the colony, but it could bring an end to the fur trade which was the best hope Plymouth had to lift its burden of debt . . . However when the call came for volunteers, Stephen Hopkins and his two sons Giles and Caleb were among the able-bodied men who offered themselves as soldiers . . . but before the Plymouth volunteers could organize themselves, the Pequot War ended."

Governing Plymouth's Citizens

Edward Winslow

Although King Charles I reigned over England and the colonies, the people of Plymouth held that they lived under a "government of laws, not of men." They chose their own officials and elected Stephen to serve as a Council Assistant (1633-36) under Governors Edward Winslow, Thomas Prence, and William Bradford. In 1636 Stephen helped draw up the "Bill of Rights" which is viewed as one of Plymouth's chief accomplishments.

The women of Plymouth benefited greatly from these new laws. While it would be hundreds of years before women could vote, serve on juries, or participate in town meetings, the women of Plymouth did gain the right to buy, own, and sell property. Their husbands could not sell property without their consent, and they were guaranteed one third of the family estate when he died. Women in Plymouth could also witness a deed or probate document, and were free to choose whom they would or would not marry.

The court, headed primarily by Separatists, also enacted numerous laws to control the behavior of its citizenry. The more the people of Plymouth sinned, the more the colony made laws to control them. It is not surprising that most of those running afoul of the law were non-Separatists who were fined for everything from public drunkenness, gambling, and idleness, to lying and swearing.

Plymouth's first criminal act was committed by Stephen's indentured servants, Edward Dotey and Edward Leister. While Stephen was off on one of his expeditions that first summer in Plymouth, the two men began to compete for the affections of his daughter, Constance. After an open quarrel, they went into the woods with swords and daggers and returned with wounds in the hand and thigh.

Dueling was illegal, and Stephen returned home to find his servants in handcuffs and awaiting trial. After finding the men guilty, Governor Bradford consulted William Brewster's book of English law which prescribed that the men have their necks tied to their feet and remain in that agonizing position for twenty-four hours in the town square.

Miles Standish

Stephen couldn't bear their suffering and implored Governor Bradford and Captain Standish to set the men free. "Within an hour," says an early record, "because of their great pains, at their own and their master's humble request, they were released by the Governor." It had been the first punishment meted out by Plymouth authorities, and would not be the last.

As a member of the Council, Stephen helped to enact some laws he probably came to regret. In particular, the court drew up strict regulations for taverns, and held the owners responsible for the conduct of their customers. Plymouth court records reveal that despite his position of authority, Stephen had his share of official difficulties.

In June of 1636, he was fined £5 for the battery of John Tisdale whom he "dangerously wounded." The court observed that he, being an Assistant, should have especially been one to "observe the king's peace."

October 2, 1637 he had two presentments before the court, the first being "for suffering men to drink in his house upon the Lord's day . . . before & after the meetings, [and for allowing] servants & others to drink more than for ordinary refreshing." The second presentment was for "suffering servants and others to sit drinking in his house, (contrary to the orders of this Court,) and to play at shovel board, & such like demeanors" for which he was fined forty shillings.

January 2, 1638 he was again presented for allowing "Old Palmer," James Coale, and William Renolds to drink to excess. According to one witness, Palmer "lay under a table, vomiting in a beastly manner" and Stephen was fined seven shillings for this incident.

June 5, 1638 he was fined £5 for "selling wine, beer, strong waters, and nutmegs at excessive rates" to the "oppressing & impovishing of the colony."

On December 3, 1639, he was again summoned before the court for having charged sixteen pence for a looking glass that could be bought in the Bay Colony for nine. On this day he was also fined £3 for selling strong water without a license.

The most serious charge Stephen faced occurred on February 4, 1639, when he was found in contempt of court and spent time in jail for refusing to deal fairly with his indentured servant, Dorothy Temple.

On showing signs of pregnancy, Dorothy was brought before the court where she named Arthur Peach as the father. Peach had recently been hanged for the murder of an Indian boy, so Dorothy and her child were left without support. Dorothy was sentenced to be whipped twice for "uncleaness and bringing forth a bastard" but this did nothing to solve the problem of support. The court then ordered that Stephen "keepe her and her child . . . during the said terme [of indenture]; and if he refuse so to doe, that then the collony provide for her, & Mr. Hopkins to pay it."

On receiving the order, Stephen said he would settle the matter himself without an order from the court. The court found him in contempt and sent him to jail. He spent four days there before Mr. John Holmes, the Messenger of the Court, agreed to take Dorothy and her son into his house for the sum of £3, thereby discharging Stephen of any further obligation for support.

After this incident, Stephen no longer sought public office and seems to have kept to his own affairs. He was, by now, the only Mayflower non-Separatist remaining at Plymouth, as Edward Winslow, Miles Standish, and others had bought property in new settlements and moved away. William Bradford said that Plymouth was left "like an ancient mother grown old and forsaken of her children."

Stephen appears in court records one last time on April 5, 1642 in regards to Jonathan Hatch who was sentenced to be whipped for "lying in the same bed" with his sister Lydia and "was taken as a vagrant, & for his misdemeanors was censured to be whipt, & sent from constable to constable to Leiftennant Davenport at Salem." A few days later it was determined that Hatch would "dwell with Mr. Stephen Hopkins, with Hopkins to have a special care of him."

End of the Adventure

Stephen found himself a widower again when Elizabeth died around 1640. His oldest children, Constance and Giles, were gone by this time, but the five younger children were probably still at home as Caleb, the oldest, would have been just eighteen.

On June 6, 1644 Stephen wrote his will and called upon his old friends William Bradford and Miles Standish to be his witnesses. He died sometime before July 17th when his will was proven. An inventory of his estate shows that he was a rich man by Plymouth standards.

Among his possessions were "diverse" books, yellow and green rugs, flannel sheets, a white cap, a gray cloak and breeches, a frying pan, funnels, fireshovel and tongs, a butter churn, two wheels, a cheese rack, four skins, a scale and weights, and two pails. His will, as it appears in Plymouth records, reads,

The last Will and Testament of Mr. Stephen Hopkins exhibited upon the Oathes of mr Willm Bradford and Captaine Miles Standish at the generall Court holden at Plymouth the xxth of August Anno dm 1644 as it followeth in these wordes vizt.

The sixt of June 1644 I Stephen Hopkins of Plymouth in New England being weake yet in good and prfect memory blessed be God yet considering the fraile estate of all men I do ordaine and make this to be my last will and testament in manner and forme following and first I do committ my body to the earth from whence it was taken, and my soule to the Lord who gave it, my body to be buryed as neare as convenyently may be to my wyfe Deceased And first my will is that out of my whole estate my funerall expences be discharged secondly that out of the remayneing part of my said estate that all my lawfull Debts be payd thirdly I do bequeath by this my will to my sonn Giles Hopkins my great Bull wch is now in the hands of Mris Warren. Also I do give to Stephen Hopkins my sonn Giles his sonne twenty shillings in Mris Warrens hands for the hire of the said Bull Also I give and bequeath to my daughter Constanc Snow the wyfe of Nicholas Snow my mare also I give unto my daughter Deborah Hopkins the brodhorned black cowe and her calf and half the Cowe called Motley

Also I doe give and bequeath unto my daughter Damaris Hopkins the Cowe called Damaris heiffer and the white faced calf and half the cowe called Mottley Also I give to my daughter Ruth the Cowe called Red Cole and her calfe and a Bull at Yarmouth wch is in the keepeing of Giles Hopkins wch is an yeare and advantage old and half the curld Cowe Also I give and bequeath to my daughter Elizabeth the Cowe called Smykins and her calf and the other half of the Curld Cowe wth Ruth and an yearelinge heiffer wth out a tayle in the keeping of Gyles Hopkins at Yarmouth Also I do give and bequeath unto my foure daughters that is to say Deborah Hopkins Damaris Hopkins Ruth Hopkins and Elizabeth Hopkins all the mooveable goods the wch do belong to my house as linnen wollen beds bedcloathes pott kettles pewter or whatsoevr are moveable belonging to my said house of what kynd soever and not named by their prticular names all wch said mooveables to be equally devided amongst my said daughters foure silver spoones that is to say to eich of them one, And in case any of my said daughters should be taken away by death before they be marryed that then the part of their division to be equally devided amongst the Survivors. I do also by this my will make Caleb Hopkins my sonn and heire apparent giveing and bequeathing unto my said sonn aforesaid all my Right title and interrest to my house and lands at Plymouth wth all the Right title and interrest wch doth might or of Right doth or may hereafter belong unto mee, as also I give unto my saide heire all such land wch of Right is Rightly due unto me and not at prsent in my reall possession wch belongs unto me by right of my first comeing into this land or by any other due Right, as by such freedome or otherwise giveing unto my said heire my full & whole and entire Right in all divisions allottments appoyntments or distributions whatsoever to all or any pt of the said lande at any tyme or tymes so to be disposed Also I do give moreover unto my foresaid heire one paire or yooke of oxen and the hyer of them wch are in the hands of Richard Church as may appeare by bill under his hand Also I do give unto my said heire Caleb Hopkins all my debts wch are now oweing unto me, or at the day of my death may be oweing unto mee either by booke bill or bills or any other way rightfully due unto mee ffurthermore my will is that my daughters aforesaid shall have free recourse to my house in Plymouth upon any occation there to abide and remayne for such tyme as any of them shall thinke meete and convenyent & they single persons And for the faythfull prformance of this my will I do make and ordayne my aforesaid sonn and heire Caleb Hopkins my true and lawfull Executor ffurther I do by this my will appoynt and make my said sonn and Captaine Miles Standish joyntly supervisors of this my will according to the true meaneing of the same that is to say that my Executor & supervisor shall make the severall divisions parts or porcons legacies or whatsoever doth appertaine to the fullfilling of this my will It is also my will that my Executr & Supervisor shall advise devise and dispose by the best wayes & meanes they cann for the disposeing in marriage or other wise for the best advancnt of the estate of the forenamed Deborah Damaris Ruth and Elizabeth Hopkins

Thus trusting in the Lord my will shalbe truly prformed according to the true meaneing of the same I committ the whole Disposeing hereof to the Lord that hee may direct you herein

June 6th 1644

Witnesses hereof By me Steven Hopkins

Myles Standish

William Bradford

Plymouth's Burial Hill Site of the Old Fort and

First Pilgrim Graveyard

In 1650 William Bradford wrote, "Mr. Hopkins & his wife are now both dead, but they lived about 20 years in this place & had one son and four daughters born here. Their son [Caleb] became a seaman and dyed at Barbadoes, one daughter died here & two are married, one of them hath three children and one is yet to marry. So their increase which still survive are 5, but his son Giles is married & has 4 children. His daughter Constanta is also married & hath 12 children all of them living & one married. One of these children was Mary Snow, who married Thomas Paine. Stephen settled in the part of Eastham now included in the town of Orleans, on the place at the head of the Cove, called by the Indians "Kesscayoganseet" and later owned and occupied by James Percival."

During Stephen Hopkin's lifetime the settlements of Jamestown and Plymouth were more reviled than admired. Jamestown was a disaster, and Plymouth was damned as a hotbed of radicals who would destroy Church and State. But these settlements, which began as mere commercial enterprises, contributed to the United State's most treasured consitutional ideals.

The tradition of representative government began in Jamestown and, echoing Stephen's declaration in Bermuda that he was "freed from the government of any man," Plymouth Colony created a government "of laws, not of men." It drew up a Bill of Rights, gave women property and dower rights, and honored a peace treaty with the Wampanoag for a record fifty years. If Stephen Hopkins had done nothing more than to help found 'Plimoth Plantation,' he would deserve a place in history.

Bibliography

Bradford, William. Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647, Samuel Eliot Morison, ed. New York, 1952.

De Costa, B.F. "Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower." The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. 133: 300-305. July, 1879.Hayward, Kendall Payne.

"The Adventure of Stephen Hopkins." The Mayflower Quarterly 51(1): 5-9. February, 1985.

Heath, Dwight B., ed., A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth: Mourt's Relation, New York, 1963 (first published in London, 1621).

Hodges, Margaret. Hopkins of the Mayflower. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972.

Johnson, Caleb."The True Origin of Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower," The American Genealogist July 1998, Vol. 73, No. 3.

Jourdain, Silvester. "A Discovery of the Bermudas, Otherwise Called the Isle of Devils." in Wright, Louis B., ed. A Voyage to Virginia in 1609. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1964.

King, Jonathan. The Mayflower Miracle: The Pilgrim's Own Story of the Founding of America, London, David and Charles, 1987.

Kolb, Avery. "The Tempest." American Heritage. 34(3) : 26-35. April/May, 1983.

Maitland, Charmian. "Stephen Hopkins in England." The Mayflower Quarterly 51(1): 7-9. February, 1985.

Mayflower Families (Vol. 6): Stephen Hopkins for Five Generations, General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1992.

Shurtleff, Nathaniel B and David Pulsifer, eds. Records of the Colony of New Plymouth in New England, Boston, 1855-1861.

Stachey, William. "A True Repository of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight." in Wright, Louis B., ed. A Voyage to Virginia in 1609. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1964.

Stratton, Eugene Aubrey. Plymouth Colony, Its History and Its People, 1620-1691, Salt Lake City, 1984

Young, Alexander, ed. Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers of the Colony of Plymouth, Boston 1844; rpt. Baltimore, 1974.